A team of scientists has managed to read, in real time, the thoughts of four people affected by severe paralysis. The device — which is implanted in the brain — is capable of capturing imagined phrases without the participants having to physically attempt to speak, as was the case in most previous similar projects.

The researchers from Stanford University acknowledge their concern about “mental privacy” and the possibility of “accidental leakage of internal thoughts.” To protect each user’s inner world, the authors designed the brain reader to activate only when imagining a complex password, one unlikely to occur in daily thought: “chittychittybangbang,” like the book and the famous 1960s children’s movie about the inventor of a flying car.

“This is the first time that complete sentences of inner speech have been decoded in real time from a large vocabulary of possible words,” Stanford neuroscientist Benyamin Abramovich tells EL PAÍS. He recalls that a year ago, a team at the California Institute of Technology managed to read inner speech in two people with tetraplegia using microelectrodes implanted under the crown of the head, but that experiment involved only eight words. Abramovich and his colleagues say their device can detect 125,000 imagined words. Their results were published on Thursday in the specialized journal Cell.

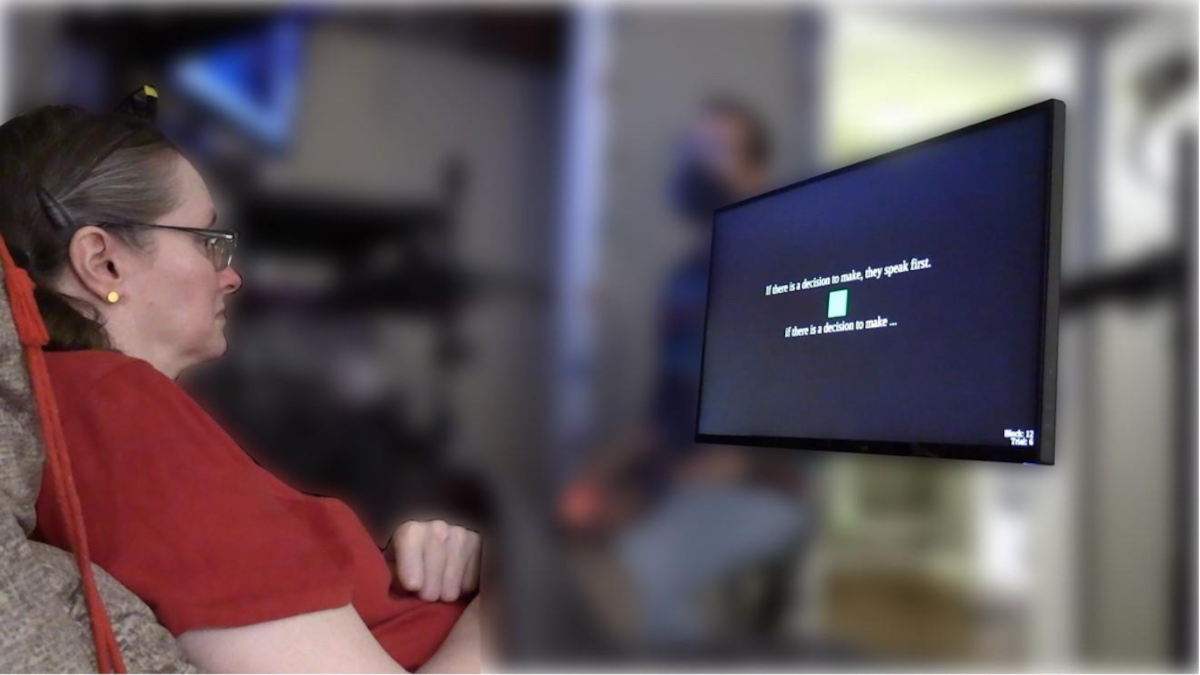

The Stanford team implanted microelectrodes in the motor cortex of three people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and a woman with tetraplegia who had difficulty speaking following a stroke. The authors claim they were able to read their “internal monologues” with 74% accuracy, without requiring participants to make the exhausting effort of trying to speak. An artificial intelligence program facilitated the interpretation of the brain signals.

“Our results wouldn’t have been possible with non-invasive technologies,” argues Abramovich, the study’s lead author along with electrical engineer Erin Kunz. “It would be like trying to record two people’s conversations inside a football stadium during a match. A microphone placed right next to them could isolate their voices perfectly. A microphone outside the stadium might be able to tell you when a goal is scored, but it’s impossible to determine the content of a person’s conversation.”

The idea of a headband-like device that could read thoughts without surgical intervention is still far off. “The neural interface used in our study can record the activity of individual neurons in the brain, similar to the microphone next to someone’s mouth inside a stadium,” Abramovich explains. “Noninvasive brain-recording technologies are like the microphone outside the stadium: they can pick up signals related to important events, but not detailed information like internal speech.”

Spanish neuroscientist Rafael Yuste visited the White House in late 2021, invited by the U.S. National Security Council, to warn about the imminent arrival of a world in which people will connect directly to the internet via their brains, using headbands or caps capable of reading thoughts. In this hypothetical future, artificial intelligence could autocomplete imagination, much like current word processors do. Companies such as Apple, Meta (formerly Facebook), and Neuralink (owned by billionaire Elon Musk) have patented or are developing wearable devices of this kind, according to Yuste, director of the Neurotechnology Center at Columbia University in New York.

The Spanish researcher recalls that two years ago, another scientific team managed to read 78 words per minute from the brain of Ann, a woman who had lost the ability to speak nearly two decades earlier due to a stroke. That group, led by neurosurgeon Edward Chang at the University of California, San Francisco, achieved 75% accuracy using implanted electrodes, but Ann still had to attempt to speak physically. A normal conversation in English is about 150 words per minute.

Yuste downplays the distinction between attempted speech and inner monologue. “I think it’s essentially a semantic difference, because it hasn’t been proven that neurons distinguish between the two cases, and there’s a lot of evidence that when you think about a movement, motor neurons are activated, even if you don’t actually execute it,” says the neuroscientist, who is leading an international campaign to have authorities legally protect citizens’ mental privacy. In his opinion, the Stanford and San Francisco experiments “demonstrate that language can be decoded using implantable neurotechnology.”

“It is urgent to protect neurological rights and legislate for the protection of neural data,” asserts Yuste, president of the Neurorights Foundation, which raises awareness about the ethical implications of neurotechnology. His advocacy led Chile, in 2021, to become the first country to take steps to protect brain information in its Constitution. The foundation has also promoted similar legislation in the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul and in Colorado, California, Montana, and Connecticut in the United States. In Spain, Cantabria is advancing the first European law to protect brain data.

Yuste applauds the Stanford team for establishing the “chittychittybangbang” password to activate their mind reader. “Including a phrase as an internal password that prevents decoding is novel and can protect mental privacy,” he says.

Neurosurgeon Frank Willett, co-director of the Stanford lab, says in a statement that the “chittychittybangbang” password was “extremely effective in preventing the internal monologue, when thought without the intention of sharing it, from being leaked.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition