Álex is 27 years old. A Mexican citizen, he arrived in the United States four years ago on a tourist visa, but never returned to his home country. In search of a better life, he decided to stay in Houston, Texas.

While he’s in the process of regularizing his status with a work visa, Álex is still one of the approximately 12 million undocumented immigrants currently residing in the United States. Therefore, he’s been added to the Trump administration’s list of “deportable” migrants. In the president’s opinion, the people on this list take advantage of the country’s generosity and commit crimes. He considers them to be undesirables.

The agreement reached between the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) will facilitate the authorities’ work in detaining undocumented individuals and moving forward with the largest deportation effort in history. This has been the Republican president’s desire for a long time. Under the agreement, the IRS will transfer information about migrants’ locations to the agents in charge of expelling them from the country. This would be possible because — contrary to popular belief — undocumented migrants pay taxes.

Like most of the names on that hit list, Alex is not a criminal. “I came here to seek a better life, not to evade the law,” he explains. And instead of abusing public resources, he finances them. Every year, he files his tax return. This has resulted in him having to pay between $1,200 and $7,000 annually, depending on his income each fiscal year. “Even if we’re immigrants in the United States, one has to abide by the laws of the country. Whether you’re in Mexico, the United States, or China, you have to pay your taxes,” he asserts with conviction.

Despite the claims made by Trump and his supporters, undocumented immigrants not only pay taxes, but they also contribute more to federal and state coffers than they receive from them. Data obtained from various sources indicates that undocumented immigrants pay between $90 billion and $100 billion in federal, state and local taxes annually. According to a report by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP), more than a third of the taxes paid by undocumented immigrants go to fund programs that these same workers are prohibited from accessing. In 2022, undocumented immigrants paid $25.7 billion in Social Security taxes, $6.4 billion in Medicare taxes and $1.8 billion in unemployment insurance taxes.

“If [the authorities] really cared about pursuing immigrants with any criminal risk, these are the last undocumented immigrants they would want to pursue. Deporting them will hurt tax collections. [And], for those who remain, attacking them for filing their returns will obviously drive them even further underground and make them afraid to pay taxes,” opined Michael Ettlinger, a partner at ITEP, at a conference last week.

It’s estimated that between 50% and 75% of undocumented households file their annual returns using the Individual Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN), which the IRS issues to non-citizens who cannot obtain a Social Security number.

By paying taxes, they comply with tax laws, which can help them regularize their immigration status by providing proof of their work history and physical presence in the United States. With the ITIN, they can also access the job market, apply for loans and even rent or buy a home.

Entrepreneurs

Álex obtained his ITIN the second year after arriving in the United States. He began working at a private investment firm, which initiated the process for him to obtain a visa. Then he had to leave for personal reasons, so his process was halted. Later, he started a marketing company, an LLC for which the only necessary identification is a passport. The result wasn’t as good as he expected, so now he’s embarked on a new venture with a synthetic turf installation company. In addition to his ITIN, he has an Employer Identification Number (EIN), which he uses to pay the company’s taxes.

Álex is concerned about what an agreement between the IRS and ICE will mean for him. “It’s going to affect a lot of people — including me — depending on what actions they take with that information. Let’s hope they don’t make any decisions as drastic as [the ones] they’ve been doing so far,” he sighs.

The dramatic images of ICE agents detaining parents in front of their children, mass workplace raids and the indiscriminate deportation of suspected criminals (who aren’t criminals) to a maximum-security prison in El Salvador don’t bode well for those who have maintained a low profile until now.

Until now, the IRS has respected taxpayer confidentiality, precisely because of the fear that personal information — especially if individuals are undocumented — could be misused. Revealing their identities would make it easier for ICE to locate them. But not filing isn’t a better option, either.

“If I stop filing my tax returns, the consequences will be worse, because now, I’d be committing another crime,” Alex shrugs.

Fewer new taxpayers

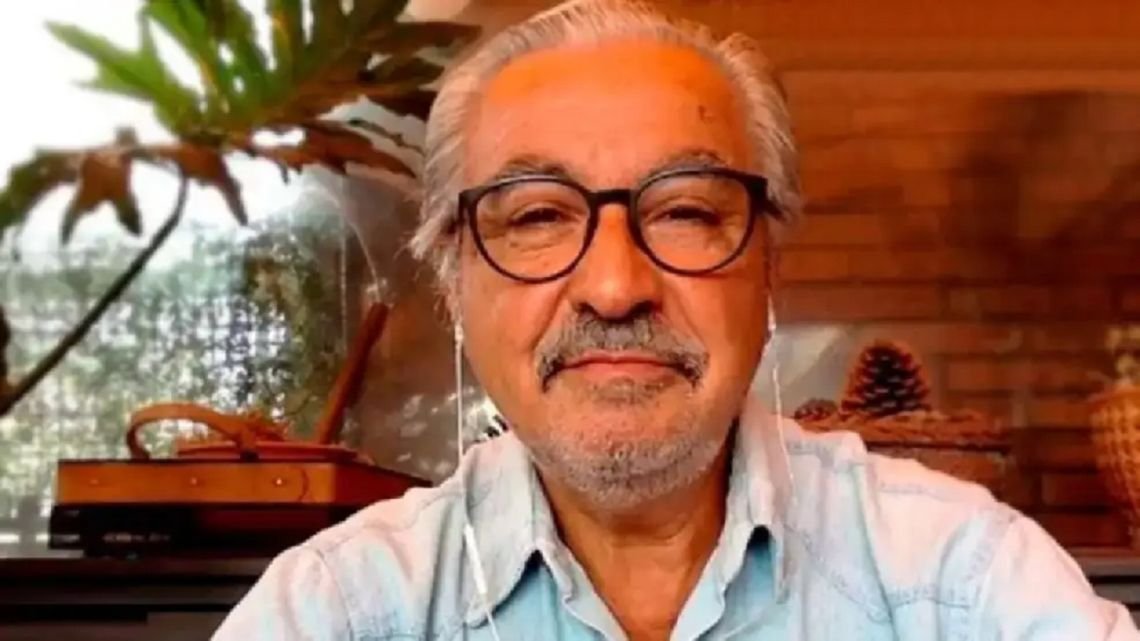

The outlook is different for those who have never filed a tax return before. Percy Peláez, president of the Central American Chamber of Commerce, has already noticed the effects of Trump’s policies in his accounting firm in Houston, Texas, where he has undocumented clients.

“Now, many people are asking: ‘If I file my tax return this time, will they give my information [to ICE]?’ The fear isn’t because they have to pay taxes: it’s because they have to give me the information. They ask me: ‘What do you think will happen with this?‘” The deadline for filing taxes ends on April 15th. The accountant’s clientele has dropped considerably compared to previous years, especially among new clients. While new ITIN applications accounted for between 12% and 15% of clients in previous years, this year, they only reached 1% to 2%.

Peláez acknowledges that offering a recommendation can be complicated. He generally tells his clients that they should follow the law, continue working and continue filing their taxes. However, he doesn’t overlook the latent risk of the authorities’ anti-immigrant crusade. “I also think about what happens if they get picked up. [Telling them not to pay would] be irresponsible [of me], but it’ll be on my conscience, right?”

Translated by Avik Jain Chatlani.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition